I do not work in higher education. I work as a mother. I work as a poet. I work part-time as a copyeditor. I work on my children’s school board, as a political activist, and for my rural, collectively-owned community. All those things are work. But because of the society in which we live, much of that work is not paid work, and I am tired. Not just tired of feeling hostage to the systems of value that have been set up and organized over time, but also tired of reinventing myself, of trying to figure shit out.

I walked away from academia twelve years ago, after completing a Ph.D. in History at Stanford and lecturing for one semester there, and never went on the job market. I knew there were many ways of being in the world that I had not had a chance to explore, and I was ready to explore them. Also, I was newly pregnant, with a husband who wanted to stay in California, and did I really want to chase precarious jobs across the United States?

In amidst the cacophony of reasons for leaving, I told myself a story, a story that many of us have heard: If you leave, you can’t go back. You must get on the publishing, tenure-track wheel right away, and keep running, or it will be too late. I was scared, but I made a choice inside that narrative frame. Not only did I never go on the job market — I told myself: This is it. No going back.

In the same year that I gave birth to my daughter, Mary Ann Mason was publishing Mothers on the Fast Track, about the way that mothers in particular often “drop out or drop down” from academic and other careers. “Leaving the fast track is not always a considered, conscious decision,” wrote Mason. “Doing so usually isn’t really a matter of choice even though some mothers believe it is.” But I did not read her book then. I was too busy, and too remote from the conversation. I see that now.

I was one of those women “leaking out of the pipeline before taking their first academic positions.” Now that I am diving into the literature on women and family and career, I feel both relieved and dispirited. I feel relieved because I see that I am not alone. And I feel dispirited, because I am not alone. I am just a statistic, and my confidence in both my memory and my autonomy has accordingly been undermined. I was not making a choice in the way that I thought I was. I was caught inside a story about women, and motherhood, and academic work.

My husband and I moved north, to a collectively-owned community in the Sonoma County mountains, and had another child. I looked into membership with the National Coalition of Independent Scholars as a way to gain access to the institutional resources (journal articles, networks, conference badges!) that I had long taken for granted inside — or even close to — the institutional setting of academia. I fully intended to revise and publish my dissertation on my own. But how does one maintain a sense of intellectual community, how does one find engaged mentorship, when one is living in the mountains and herding toddlers full-time? I got overwhelmed. I worked for a short but precious stint as a freelance editor on an academic manuscript, waking up at 5am to edit and email the author, when I hadn’t already been awake three or four times during the night. When my children were a bit older, I looked for other ways to keep my mind engaged and alive. I started the Occupy Santa Rosa Free School, organizing and facilitating teach-ins in Santa Rosa’s public square all summer long. But that ended with the slow burnout of Occupy in general, and my own rather devastating activist burnout, too.

This is the texture of life. This has been my path, and I own it. And yet, and yet… recently something has been bubbling up, a loud and fervent desire that I try not to name regret. A crack has been opening in that story I have for twelve years been telling myself. I miss history. I long for sustained (and paid) intellectual community, the flashes of inspiration and insight that fly between scholars, I long to share what I know and have to offer from all those years of study, and I long for the archives. I recently took my daughter to Stanford for the first time since we moved away. Through her eyes, I saw sharply how much I had given up. I harbor no illusions that I will ever work in or near an institution quite so wealthy and privileged ever again, and I am not sure I even want to. But I do want, at age forty-five, something that the story told me I could not have.

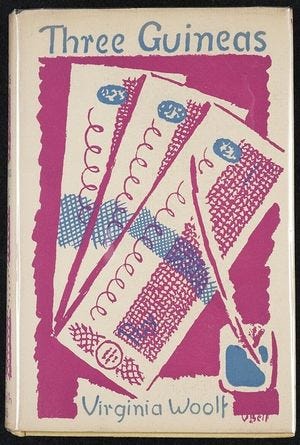

In Three Guineas, a brilliant, scathing, and sadly still relevant 1938 essay on feminism and militarism that explores how women can enter into institutions built by and for men, Virginia Woolf also wrote about wanting, about desire. Despite all the obstacles, despite the enormity and monstrosity of systems that sometimes feel impossible to see let alone transform, a thread of desire ran (and runs) through women’s lives. There is so much that women wanted (want), above and inside the “tumultuous clamour” and refrain of prohibition: “You shall not, shall not, shall not….” —

[The] desire for knowledge…. Also the desire for an open and rational love…. But again the desire not to love, to lead a rational existence without love…. to travel; to explore…. to learn music, not to tinkle domestic airs, but to compose….to paint, not ivy-clad cottages, but naked bodies. They all wanted…. it was not freedom in the sense of license they wanted; they wanted…not to break the laws, but to find the law.

They wanted to rewrite the story of what was considered normal and possible, against the formidable backdrop of “Nature, law, and property.” They wanted to revalue motherhood, a profession with no name and no salary (“Is the work of a mother, of a wife, of a daughter, worth nothing to the nation in solid cash?… wives and mothers and daughters who work all day and every day, without whose work the State would collapse and fall to pieces….Can it be possible?”) They wanted to build networks of their own, outside of the stale ideas of “culture and intellectual liberty” they were so often asked to defend, and freed from the expense and exhaustion of exerting indirect influence via well-placed marriages and expertly-managed salons. And they wanted to pay the bills. (The “answer given to us by biography would be short but sufficient: have I not to earn my living?”)

I want all these things, too. Still. I know it’s complicated. But undeniable.

And so I invoke that “obstinate and perhaps irreligious desire” for what I am told I can’t have and start exploring possibility. After returning from that trip to Stanford, I sit down and scroll through Facebook. Facebook fills a need for me, a need to fight the isolations of primary caregiving and rural living by keeping me connecting to academic and activist friends. My dissertation, completed in 2005 at Stanford, was in part about the ways that people from the British colonies utilized technological networks of steam travel for their own purposes, raising questions about subjecthood, borders, and belonging in a increasingly integrated though unequal world. So yes, Mark Zuckerberg might be a jerk. Yes, Cambridge Analytica, the alt-right, and Russian hackers use the platform to sow hatred and confusion. Yes, I am addicted to the dopamine rush. But yes, also, to using the technological networks available to us for variant, unruly, and sometimes radical purposes. Yes to the liberating impulses of gossip, to curiosity, to conversation across borders. Yes to using social media for your own reasons and for collective liberation, too.

I am a member of a Facebook group of feminist historians. I was invited by a friend who knew I was looking for a way back in. Knowing that as a non-academic I was an outlier in the group, I posed this question, and hit send:

Do you know of a single woman who has taken time off, like really taken time off, over those precarious childbearing years and then managed to start publishing, teaching, working in academia again? If you do, I would like to know her. If you are this woman, I’d like to talk. If the answer is no, all-around, then I would like to either burn the f*&king walls down and make it happen, because I am filled with a sort of regal, rageful desire, or publicly grieve and figure out how to move on, with your loving, fierce, feminist support. So let me know.

And then I went to muck horse corrals. Because when you live in the country that’s what you do after asking a vulnerable question. You do some physical work or go for a long walk and wonder if you were too impulsive, whether you should even bother to check for a response. But…response there was.

When I returned to Facebook the comment thread was growing, not only with examples of women historians who had left the academy and returned or otherwise followed non-traditional career paths (Gerda Lerner, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Leslie Peirce, Mae Ngai, Karen Spalding, Sarah Hanley, Amy Swerdlow, Glenna Matthews, Elizabeth Fenn) but also with personal stories, side conversation, ideas, recognition, and support. Within the space of three hours, I found out about the one fellowship available to women historians with non-traditional career paths (the Prelinger, offered by the Coordinating Council of Women Historians), I was invited to a conference of women historians relatively close by (I’m finishing this piece in my hotel room at said conference, gloriously alone and quiet), and was contacted by the chair of a nearby department, asking for my CV. Again, I harbor no illusions. Because I am also a member of an online group of women who have left academia, because of the lack of support for parenting, because of sexual harassment, because of the precarity of part-time, adjunct, hamster-wheel work, because of unhappiness. So I have my eyes wide open, knowing that in the roughly twenty years since I began my Ph.D. the historical profession has been eviscerated along with much of higher education. As one woman historian wrote to me privately, many of those “re-entry” women were from “an earlier generation and a different market.” I have read Erin Bartram’s searing blog post on the grief of not acquiring a job, and the unacknowledged grief of loss in the field. I know that even women who stay present in their professions tend to drop into a “reduced-hour, underpaid second tier,” and have trouble crawling back out. And I have read Sylvia Ann Hewlett’s work on the plethora of “off-ramps,” and paucity of “on-ramps,” for women who even temporarily want a non-fast track career. As another woman wrote, “Is it an easy path? No. Will you get the job of your dreams? Likely not. But, how many people these days can be confident in that anyway?”

I am listening. And still I am committed to changing the story.

But all writers know that you can’t revise a story all at once. You have to work on one part at a time, the part that is rising up to meet you. Sometimes it’s obvious where to begin. Sometimes it’s just the part that you make yourself sit down at the computer to deal with, and it’s strenuous. So one day I join the Stanford Alumni Association to gain access to online journal articles, and that feels like progress. Another day, I survey my dissertation chapters and decide which ones are closest to publication quality, and that’s amazing. I reach out to local universities and community colleges about adjunct work, feeling conflicted about participating in the system of evisceration but knowing I need to start somewhere. I no longer feel like I need to find or create a perfect Outsiders Society, which Woolf rather cheekily proposed as a way to sidestep the challenge “of making room for ourselves within structures built by and for men.” (These were historian Amy Woodson-Boulton’s words, on that Facebook thread.) I dare to hope that instead I can, as Woolf declares at another point in the essay, not thoroughly “burn the house down, but make the windows blaze!”

Toby Ditz, a historian of early America at Johns Hopkins, chimed in on Facebook, too, and admitted to feeling tearful. “I have had the very great good fortune to be able to follow a rather conventional tenure track career line,” she wrote. “But I stand on the shoulders of magnificent fierce women who fought their way into academia from the margins against all kinds of obstacles.” She told the story of her mother, one of only two women to graduate Columbia Law school in 1951, with Toby as a baby of only three weeks old in her arms. Ditz continued:

Her law career then followed all kinds of twists and turns, including several years off to raise kids, some years as a volunteer lawyer and some years in part time work, until, as she put it, in her early 50s she picked up her brief case, put on her high heels, and went downtown to work full-time for a big insurance firm in New York City as a tax lawyer. She never looked back. When at the firm she said in a speech to the younger women in the company — using herself as exhibit #1 — that ‘women end up having to invent their lives’ (for all the structural reasons we can name) — and also that ‘it is never too late.’ ‘It is never too late’ — she repeated that phrase like a refrain several times. It should not have to be this way. Still. It is unjust. It exacts psychic wounds. But we persist. So, here’s to ‘invented’ lives.

Yes. Here’s to the unruly, highly personal navigation of institutions and networks. Here’s to new stories and incessant desire. Here’s to fabulously invented lives.

Soon enough, perhaps, I’ll see you on the printed page, or in the classroom.

Yes, yes, yes! Wishing that you find the satisfaction and challenges you are craving. XO